Key messages

- NHS Continuing Healthcare (CHC) is care that is funded by the NHS in England but provided outside of hospital for people with significant ongoing care needs. CHC is organised into two streams – standard and fast-track, the latter for people whose condition is rapidly deteriorating, many of whom may be approaching the end of life.

- As of 31 March 2024, the total number of people in England eligible for CHC was 52,096, made up of 34,055 via the standard route and 18,041 via fast-track.

- To be eligible for CHC, people must undergo an assessment to determine the extent and severity of their needs. Between 1 January 2024 and 31 March 2024, just over a fifth (21%) of people who were assessed for standard CHC were found eligible, although this varied from 7.3% in Gloucestershire ICB to 42.5% in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland ICB.

- There is also wide variation in the numbers of people assessed as eligible for CHC. Over the course of the year from 1 April 2023 to 31 March 2024, this ranged from 36.9 people per 50,000 in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly ICB to 301.0 per 50,000 in Lincolnshire ICB.

- CHC is a complex and often daunting process for individuals and their families. Previous research has shown there is a lack of awareness about CHC, and people experience challenges with the process such as a lack of understanding about particular conditions and delays.

- Wider challenges facing our health and social care system have a significant impact on CHC. This includes the precarious nature of the provider market, stark workforce shortages and funding pressures. CHC is a window into the stark divide in our system between care that is funded by the NHS and care that isn’t, and its importance in wider debates about what we need from our health care system now and in the future should not be underestimated.

The line between health and social care has always been a difficult one to draw. Since it was founded, NHS health care has been free at the point of use. But social care is means tested and the responsibility of local authorities. This means that whether people receive state-funded support or not depends on their financial situation.

NHS Continuing Healthcare (CHC) in England emerged initially in the early 1990s as an attempt to address the situation that saw people requiring support outside of hospital falling between the two, with families facing significant costs for the care they needed. Initially, local areas adopted their own approaches before a national framework (which aimed to ensure greater consistency) was produced in 2007.

What is NHS Continuing Healthcare?

CHC is a package of health and social care provided outside of hospital, such as in a care home or an individual’s own home, which is arranged and funded by the NHS. It is for individuals over the age of 18 who have significant ongoing care needs that arise from a ‘primary health need’. CHC is organised into two streams – standard and fast-track, the latter for people whose condition is rapidly deteriorating, many of whom may be approaching the end of life.

CHC exemplifies many of the persistent questions about how to fund care for people with long-term health and care needs. But awareness and understanding about what it is and how it works remains limited among the public, and even among some health and care professionals. Despite numerous investigations and recommendations for improvement, CHC remains a significantly complex and challenging process.

This explainer seeks to describe how eligibility for CHC is decided, the trends in the latest national data, and highlight some of the key issues. It draws on data analysis, document review and conversations with national stakeholders. It focuses on England, although a brief summary of how CHC (or its equivalent) is approached in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland can be found here.

Who can be eligible for CHC and how is that decided?

Eligibility for CHC is based on whether someone is assessed as having a primary health need, although in practice that is often far from clear-cut. It could include people with long-term disabilities since birth or through accidents or illness, people with progressive conditions such as dementia or Parkinson’s, those approaching the end of life, and older people with frailty.

If someone is assessed as eligible for CHC, the integrated care board (ICB) is legally responsible for covering all of an individual’s assessed health and social care costs. Those found ineligible for CHC can be faced with a cliff edge of potentially catastrophic costs for the social care they need. Or, if they fall under the financial threshold during the social care means test, the local authority may be required to pay the costs of their care.

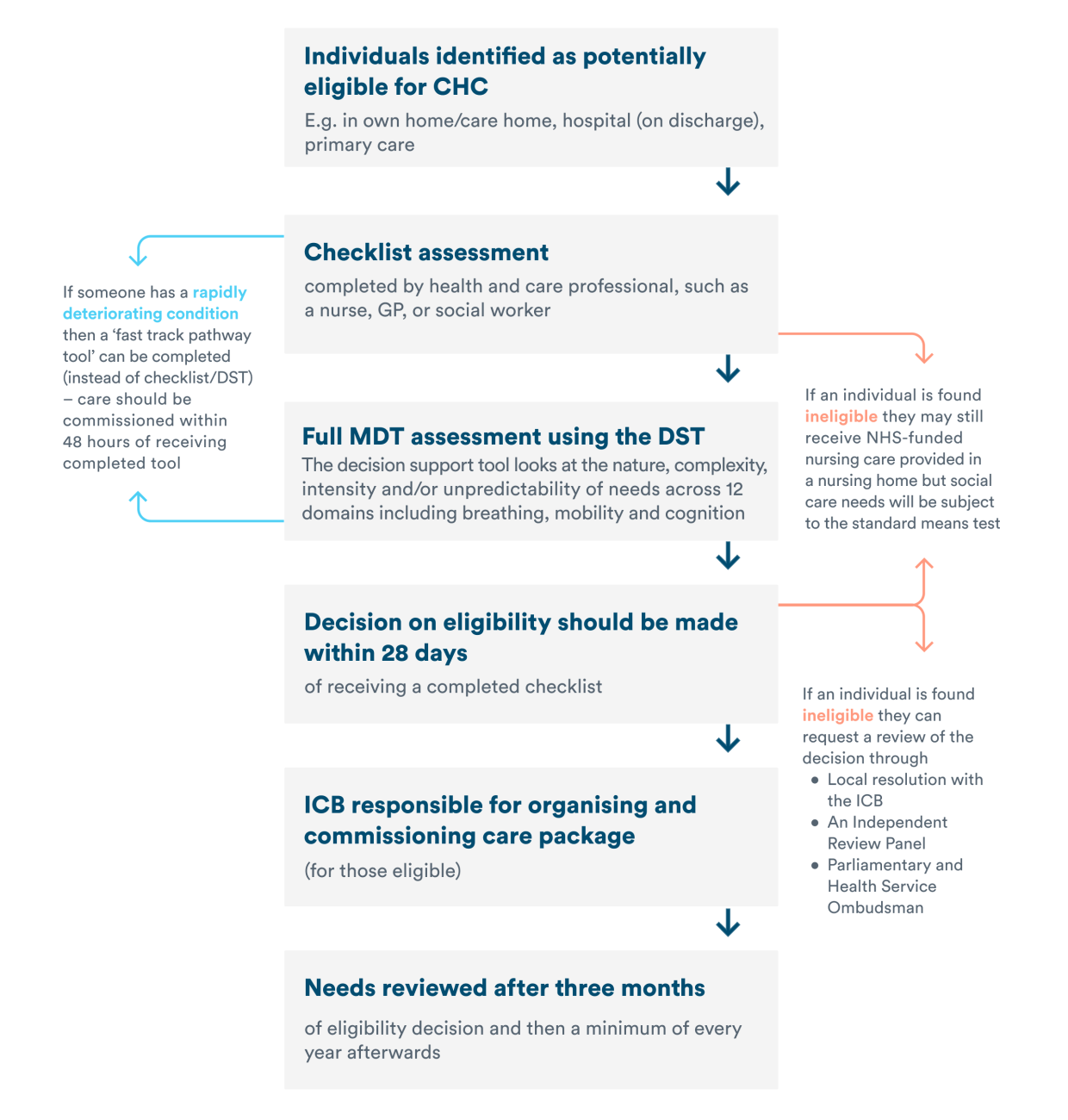

Since it first emerged (at a local level), there have been attempts to standardise how CHC is implemented, and key principles are set out in the national framework. The eligibility process should follow what’s set out in the diagram below. For standard CHC, most individuals are assessed initially through a ‘checklist’ that determines whether they require a full assessment.

What happens if someone is found eligible for CHC?

ICBs are responsible for commissioning, planning and managing care for people eligible for CHC. This can be provided in a residential, nursing home or in a person’s own home, and cover for example care workers, support with daily activities, equipment or care home fees. Adults in receipt of CHC also have a legal right to a personal health budget (PHB). In practice, however, what support is arranged depends on which services are available locally, which is influenced by the local social care market.

For CHC to operate effectively, collaborative working between NHS organisations and local authorities is vital. This includes when identifying individuals who may need support, conducting assessments, and organising the provision of care. An integrated and person-centred approach is key.

What does national data tell us about eligibility and access over time?

NHS England publishes quarterly data on aspects of the CHC process and, while limited in what it can tell us about individuals receiving CHC, it points to a number of trends.

An increasing proportion of assessments taking place are for fast-track CHC

While the number of fast-track assessments per quarter has increased from 22.9 per 50,000 to 27.0 per 50,000 since mid-2017, the number of standard assessments completed per quarter has fallen from 16.5 per 50,000 to 12.6 per 50,000 by March 2024. That means that 24% fewer people were assessed for standard CHC in quarter 4 of 2023/24 when compared to quarter 2 of 2017/18, while there was an 18% increase in the number of people assessed for fast-track. The precise reason for this increase is unclear, but it does raise questions about whether people are receiving support at the right time, and not only when their condition has deteriorated significantly.

Covid-19 interrupted CHC assessment processes, as can be seen in the chart below, but those trends had already begun before Covid hit. It’s also notable that fast-track numbers had returned to pre-Covid levels by late 2022, but standard CHC numbers continue to remain lower than pre-pandemic levels.

The assessment conversion rate for standard CHC has fallen over time

The proportion of people who have undergone assessment and are then found eligible for standard CHC (the ‘assessment conversion rate’) has dropped from 27% to 21% since mid-2017. This means that, by early 2024, only one in five people undergoing assessment were deemed eligible for a standard CHC package.

The overall number of people being assessed as eligible for CHC has also fallen over time

Because people are continually being assessed while others no longer require care or become ineligible, the total number of people eligible for CHC changes constantly. As of 31 March 2024, the total number of people eligible for CHC was 52,096, made up of 34,055 via the standard route and 18,041 via fast-track. The chart below shows the numbers of people found eligible for CHC – both standard and fast-track. (Note that CHC assessments were suspended from April to August 2020 during the first wave of the pandemic, to support the need to free up hospital spaces and speed up discharge.)

Falling eligibility for standard CHC could, similarly, suggest that fewer people are being assessed as meeting the criteria, raising concerns about how well people with complex long-term needs are being supported. The NHS Confederation recently recommended that DHSC review the current checklist, however, due to concerns that it raises expectations about eligibility.

It’s important to note that this data only tells us about those who are referred for CHC. What we don’t know is how many people may not even be undergoing a checklist assessment and reaching the referral stage. This is something that has also been identified in relation to other types of social care support.

The numbers of people eligible for CHC varies widely across the country

Numbers eligible during a given period also vary widely between ICB areas. In the year to March 2024, total eligibility (standard and fast-track) ranged from 36.9 per 50,000 population in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly ICB to 301.03 per 50,000 in Lincolnshire ICB. Between 1 January 2024 and 31 March 2024, just over a fifth (21%) of people who were assessed for standard CHC were found eligible, although this varied from 7.3% in Gloucestershire ICB to 42.5% in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland ICB.

Variation is not a new issue and will be influenced by several factors. This includes local demographics, population need and the availability of locally commissioned services. But the variation in eligibility is substantial, and suggests there are inconsistencies in how the national framework is interpreted and applied at a local level. Although there are pockets of good practice, the inconsistency raises questions about fairness and creates significant uncertainty for families.

People are waiting longer than they should to hear about eligibility

The national framework specifies maximum limits for the time that someone should wait to hear about whether they are eligible. However, the data indicates that delays are commonplace. As of 31 March 2024, 1,730 referrals were incomplete and had been delayed by more than 28 days. This included 612 people who had been delayed by an additional two weeks, and 40 who had been delayed by over 26 weeks.

Reasons for delays are not recorded, although factors could include disputes between the NHS and local authorities over eligibility decisions, backlogs in assessments and staffing pressures. The data also only records delays between referral and assessment, and does not record length of time waiting for a checklist or waits to receive a care package once someone is deemed eligible, which could also be significant.

What is the impact on individuals, carers and families?

CHC often arises at a challenging time for individuals and their families, and the stakes are high. If someone is not eligible, they are potentially liable for all of their social care costs. But awareness among the public that this is a possibility is low. In general, around 47% of the public believe social care to be free at the point of need.

Previous research has explored the experiences of patients and their families, including investigations by the APPG on Parkinson’s and the Continuing Healthcare Alliance. These identified, among other things:

- A lack of awareness or information on the process

- A lack of involvement of the person or their family, or people with specialist knowledge of the person and their condition in assessments, and inconsistent use of the Decision-Support tool and Multi-Disciplinary Team, and:

- Delays between referrals and decisions on eligibility.

People have a right to request a review of eligibility decisions and can do so via a three-stage process, beginning with local resolution at ICB level, followed by an Independent Review Panel and then the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman (PHSO). In Q4 of 2023/24, there were 596 local resolution requests, of which 13% resulted in eligibility. Details of these cases are not published, but that represents around one in six eligibility decisions being overturned following challenge at a local level. Outcomes of appeals at Independent Review Panel – the next stage of the dispute process – are also recorded but not widely available.

Outside of this, there is currently no systematic collection of patient experience or patient-reported outcomes on CHC. But the PHSO publishes details of its investigations that provide important insights. One issue recently highlighted by the PHSO as a result of their investigations were people needing to top up care costs due to issues in care planning. More generally, they highlight the significant uncertainty and distress that individuals and families can experience regarding their loved ones’ care.

Stakeholders also raised concerns that there may be significant inequalities in accessing CHC but, given that national CHC data does not record demographic information, it is difficult to ascertain this. NHS England is developing the NHS CHC Patient Level Dataset, which should help provide a greater understanding, although this is still in the early stages. There are also concerns that people with certain conditions are particularly disadvantaged by the CHC assessment process.

Why does this matter?

CHC is care that is funded by the NHS, and the wider challenges facing our health and social care system have a significant impact on CHC. This includes the precarious nature of the provider market, stark workforce shortages and funding pressures. More generally, satisfaction with social care is the lowest it has ever been, with 57% of respondents to the recent British Social Attitudes’ survey reporting they were dissatisfied with social care.

As outlined earlier, CHC is an area where local collaboration between the NHS and local authorities is essential, and effective relationships are key to this. The NHS Confederation recently noted that to support this there needs to be not just better data sharing but also clearly defined responsibilities and expectations, and better alignment with other areas of responsibility such as the Care Act.

With an increasing and ageing population, and people living longer with multiple complex needs, there are significant questions about how to best fund and provide care for individuals who need it. Between 2015/16 and 2022/23, spending on continuing care across the NHS increased from £4.3 billion to £5.9 billion, with the budget for 2023/24 set at £6.5 billion, likely reflecting factors such as the increased cost of care and increased complexity of needs for those eligible. It is imperative to think long term about how to design and implement services so that people requiring support can access it when required.

At a national level, DHSC has stated that there are no plans for a wider review of CHC, although work is ongoing to improve the CHC process. It is also interesting to note that in their recent implementation plan for a national care and support service, the Welsh government committed to review their CHC policy.

At the heart of it are individuals and families faced with a complex, daunting process at an intensely emotional and challenging time. CHC is a window into the stark divide in our system between care that is funded by the NHS and care that isn’t, and its importance in wider debates about what we need from our health care system now and in the future should not be underestimated.

Next steps

This work set out to describe the CHC process and latest trends in the national data, as well as highlight some of the key issues. Over the next few months, we will be conducting more in-depth mixed-methods research to explore variation and inequalities in relation to CHC in more detail. More information can be found on our project page.

Limitations of the data

- Although we have examined the publicly available data, it is subject to limitations. Firstly, data is based on people’s date of eligibility, rather than when they received funding or care. This makes it difficult to draw conclusions regarding the time it takes for funding to be put in place or for care to be delivered. It also does not include the time taken to obtain a checklist.

- The data also does not include any information regarding the demographic characteristics of who is assessed, or assessed as eligible for CHC.

- Figures on delays are based on ongoing activity, some of which is carried over from previous periods, so it is unclear what proportion of overall referrals and assessments this represents.

Suggested citation

Hutchings R, Davies M and Curry N (2024) “Falling through the gaps? A closer look at NHS Continuing Healthcare”, Nuffield Trust explainer